Where did common sense go?

- Angelika Sosnova

- Jul 31

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 1

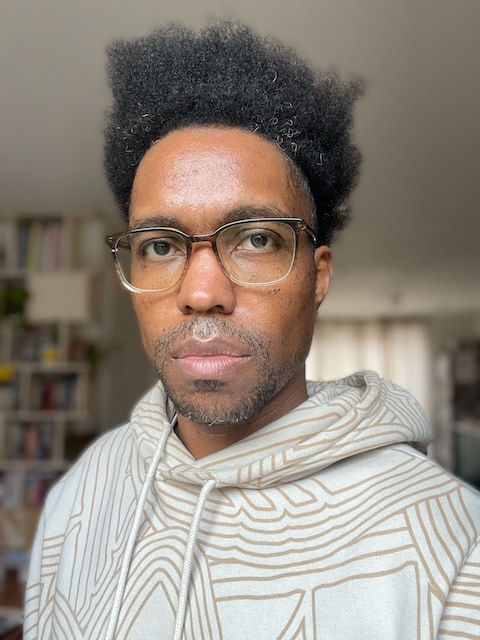

Today’s interview with Qa’id Jacobs tugged on the deepest strings of my heart. The conversation went from migrant life struggles to existential crises and the moral choices of a designer. Make yourself a nice cup of tea and enjoy the story.

Qa’id grew up in Englewood, New Jersey, a city in the suburbs of New York. He is a hugely passionate designer and thinker. With this introduction, I’m giving the floor to him now.

‘I studied music and business administration in the music industry at NYU: all you need to know to run a music record label, for example, or manage a recording studio. And I did precisely that after graduating for a while. Then the music industry started to wane…’

‘I feel it’s what’s happening to the software industry in the NL in the 2020s. There are fewer opportunities every year after the Covid pandemic, many layoffs, more candidates that cannot find a position.’

‘I’m thinking of moving towards front-end development. It shouldn’t take long to educate myself on the inner workings of the most popular front-end frameworks. I might take a course or two.’

‘Yeah… Front-end skills are in high demand.’

‘So, in 2001 or two or three, in New York, the economy was really shit. And the music industry started to shrink inside the city. My opportunities dwindled. I lost my job. At the same time I realised that I didn’t have the right type of personality to succeed in the music industry (the one that doesn’t mind the game of aggression). For a while afterwards I busied myself with small freelance projects like directing online traffic to an artist or a show. And little by little I learned web design, user experience design, user interface design. Two or three years after leaving the music industry, I found that I could make a decent living from that work.’

‘That’s a rational, economically valid choice—switching away from a suffering industry. But then you decided to leave the country too. Why? I mean it’s a lot of work and stress to uproot yourself and move overseas.’

‘Yes. [Smiles.] I thought it would be easier. I thought picking up a Germanic language would be a piece of cake, the same as learning the spoken and unspoken rules of a new country. It wasn’t….

‘But you asked about my reasons. As a black American, our history in the United States is mostly obscured, partially erased, tucked away into dusty corners of municipal libraries and archives. It started with my mother and my sister doing some heritage research. They were able to track our family history through a list of names in old registers and inventory books). Those findings struck me. I realized there wasn't a lot of difference between what people were experiencing 300 years ago and what I was experiencing on that day; realising that we were still stuck in the shadow of America's colonial behavior. I thought of what I could change, how I could exercise better access to information and my freedom to move around, rights my ancestors didn’t have. Turns out there were plenty of jobs for web and product designers outside of the U. S.’

‘Were you looking for a blank slate to start a family history anew?’

‘To extend my family’s geographical footprint, to make new space outside of the shadows of colonialism.’

‘Did it work?’

‘Mmmm. Europe isn’t free from racism but I never felt as safe in Brooklyn as I do in Amsterdam. When the opportunity to move abroad presented itself, it was the three of us: I, my partner, and my one-year-old son. Back in Brooklyn, I’d go to work every day with an ever present feeling that I might not make it back home. Bad shit happens every day. It makes you anxious, worn-down, paranoid. Just to give you an example: getting some cash from an ATM machine in Brooklyn was a risky enterprise that demands you be extra vigilant. Find a machine, observe if people use it, figure out if the machine has been hacked, use the eyes on the back of your head to scan the surroundings. I did just that in Amsterdam once, and when I felt a movement behind my back, I turned around prepared to scrap…. but it was just an old lady that took her place in a queue to use that ATM, right behind me.’

‘I know the feeling. In Russia we say that if you aren’t paranoid it doesn’t mean that you aren't being followed. [We both lauth.] Dark humour.’

‘Where would you go, if you had to migrate again?’

‘I’m actually thinking about it a lot, because I don’t want to stay here for another 12 years. My ideas are going in the direction of countries with diverse populations, specifically with more black people. It might be Kenya (Nairobi) in Eastern Africa, Ghana or Senegal in West Africa. I enjoyed travelling to Dakar. The economic state of those places is a big part of my considerations. And wherever I go next, I don't want to be a gentrifier. That's the factor that is the most complex for me in this question.

‘Years of being separated from my family taught me to plan that ahead as well. In all these years I've been in Amsterdam, my mother visited me just a couple of times, and my sister with whom I grew up—not even once. A new place should be easier for my family to visit.’

‘How did your expectations fare against the reality of being a black American migrant?’

‘My expectation was that things would be easier. Yeah, I was going to have an easier life [smiles.] and make more money than before. Social isolation hit us the quickest and the hardest, it put a lot of stress on my relationship with my partner. I mean, we had a few acquaintances in Amsterdam, but building true connections takes time while loneliness envelops you almost in an instant. Every (small) problem had a significant impact on us because we didn’t have a sanctuary. When you have a home and all your favourite things in it, it soothes you, heals your mental wounds, gives you energy. A migrant doesn’t have that, at least for the first few years. So, yeah, it was really hard. For how long? Oh, my gosh. Some of those challenges still exist. But I would say, it took us five years to feel good in Amsterdam, to figure out how to use money here, how to properly navigate its financial reality.’

‘About racial discrimination. Do you feel it’s more or less present here in the Netherlands compared to the states? How do you even know that you are being discriminated against?’

‘Yeah, that's a good question. You don’t always get direct, overt evidence, which makes it not only difficult, but also anxiety inducing. Because the question you might ask yourself is, “am I seeing something that's not there? Am I able to ignore that feeling of being unequally treated in every interaction I have? Am I being paranoid about the world?”

‘For me it feels like I am not high on the list of targets for racism in the Netherlands. They have their own demonized groups of non-white people. There's definitely islamophobia here. So, yes, some forms of race- and nationality-based discrimination is pretty evident. But if I compare it to the U. S., it never leads to life threatening situations. I have been offended by situations with evident discrimination, but I have never felt physically threatened. When it’s like, oh shit, we better get out of here. Something's about to go down.

‘I think that’s the Dutch welfare state at work. Most people have enough money to avoid becoming completely desperate. People aren’t often at risk of dying from hunger or cold. There are enough resources to keep them from having to take from others to cover their own needs.’

‘I know what you mean. In the 1990s and early 2000s in Russia, it was everyday business that someone got killed or seriously injured for the contents of their pockets (for the equivalent of a bottle of vodka). What a miserable death—to be killed for your pocket money. [Very dark humor.]

‘I guess, we just need to feed the poor and crime rates will go down.’

‘Sounds about right.’

‘On a lighter subject. Let’s talk about design. We are both product designers. I’d love to hear your opinion on the subjects that bother me. This one, for instance: are product designers a necessity or a luxury? Let me explain. I worked at several companies that didn’t have enough designers and refused to see that as a weakness in their business strategy. More than that. When those companies optimise profits, they immediately dispose of their product designers.’

‘This is a hard one to truly debate – it feels off to argue against the confirmation of my craft.’

‘I accept your biases. You are a designer and you are biased. I also feel that justifying the importance of my profession has taken way too much time of my professional life. Why so? Isn’t the need to consider a user while making a product for them self-evident? Would you like to buy a T-shirt or a device that no one designed?’

‘No, I wouldn’t. Still there are products for which a designer isn’t a necessity.’

‘Maybe in e-commerce. But only because good design standards have become common knowledge by now. There are just a few golden rules: detailed product presentation, few purchasing steps, emphasis on secure financial transactions. Right? The world of B2B (business-to-business) users is a different one. Those users never pick software to work in and they are deprived of the opportunity to complain.’

‘That's an excellent time to put on a hero cape and go in! I do it myself. My poor corporate user is stuck in the system of shitty suboptimal software his boss decided to pay for. And instead of trying to convince anybody that the user experience needs to be improved, I make it possible for the user to express their hatred. All I need afterwards is to connect that sentiment to the bottom line. Of course it’s tough for the user to be able to tell a business leader how their bad feelings are making the organisation less money.’

‘Exactly! Which reminds me of another issue from my work life. When you interview for a vacancy, they often demand you to have experience in the same industry as their own product. Strange. Because the design process is the same. It could be a physical object, a service or a software application, made for finance, healthcare, education, you-name-it—, the design for all of them goes around user needs, limits, expectations, capabilities. I’ve become hoarse explaining that on every job interview to no result. Why is it so?’

‘The thing is that your thinking uniquely operates on a high level of abstraction. Where an untrained person sees a series of messy screens, you see time-task optimization possibilities. Of course they think you are crazy. They know that the automotive industry is different from the pharmaceutical industry. Even though none of that matters in our product design reality. We just need to support the choice-making work-flow. I totally agree with you, and it's frustrating for us. Maybe it’s useful to think about how the consequences for a company are much greater; by hiring people with similar backgrounds and similar (limited within one industry) work experience, they keep innovation away from their products.’

‘I just realised I have so many complaints about my profession. Let’s look at the positive side. Would you recommend someone to become a designer?’

‘Yes, absolutely! As designers, we are uniquely equipped to not only find problems but also solve them, to generate possibilities. If I didn’t have a designer’s lens through which to look at life, I wouldn’t be able to figure out many things. And I presume, I’d feel more depressed. The designer’s mindset is a fundamentally optimistic, enthusiastic and curious one. It’s a joy to own it. You are inevitably aware of the endless possibilities in front of you, you have skills to observe, to analyse data, and to synthesise conclusions. If you can design a service or a product, design the best experience for your own life.’

‘The last question for today. What’s the role of design in the time of war?’

‘It’s on both sides, isn’t it? One side is designing the most effective offence and the other—the most effective defence. The news narrative is being tailored depending on if a country is our ally or enemy. The perspectives are being bent.

I watched a news report on the exchange of the soldiers’ bodies between Russia and Ukraine. In the footage, I noticed that the workers’ overalls and the bags in which the bodies came were made of the same fabric with the same-looking seams. And I thought, “that was someone’s task for the day – a design job to coordinate the tools of the Undertaker.”’

‘That gives me goosebumps.’

‘Me too.’

Comments